Key competences in initial vocational education and training: digital, multilingual and literacy

published: 15-02-2021

People who to some degree master the so-called key competences literacy, digital skills and multilingual have lifelong advantages over those who do not. Key competences such as literacy, digital skills and languages are important for personal development, employment, integration into society and lifelong learning. They are transversal and form the basis for all other competences. However, more than one in five 15-year-olds in the EU still have low reading skills, a striking 43% of Europeans do not have basic digital competence and around a third of employees who need digital competences are at risk of skill gaps.

Acquiring key competences is possible through various learning pathways, including vocational education and training (VET). However, little is known at the European level of how VET supports the key competence development. The European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) recently published the research paper “Key competences in initial vocational education and training: digital, multilingual and literacy” (Cedefop, 2020). Panteia (consortium leader), in collaboration with 3s Unternehmensberatung GmbH and Ockham IPS conducted preliminary analysis and drafted their findings for this paper.

The overall purpose of this study was to investigate the implementation of VET policy priorities, as defined in the 2010 Bruges communiqué and the 2015 Riga conclusions in the EU-27 (+ Iceland, Norway and the UK) and to contribute to continuous learning in VET policy development. The study analysed the relationship between policies related to promoting three selected key competences (literacy, multilingual and digital competence) in IVET adopted in 2011 to 2018 (research question 1) and the embeddedness of key competences in IVET (research question 2). In analysing the relationship, the question was answered to what extent promoting key competences in VET have been effective and efficient at national/EU level (research question 3).

The study analyses the extent to which digital, multilingual and literacy competence are included in initial upper secondary VET (IVET) in the EU-27, Iceland, Norway and the UK, as well as national policies supporting their development since 2011. It focuses on four areas of intervention: standards, programme delivery, assessment and teacher/trainer competences.

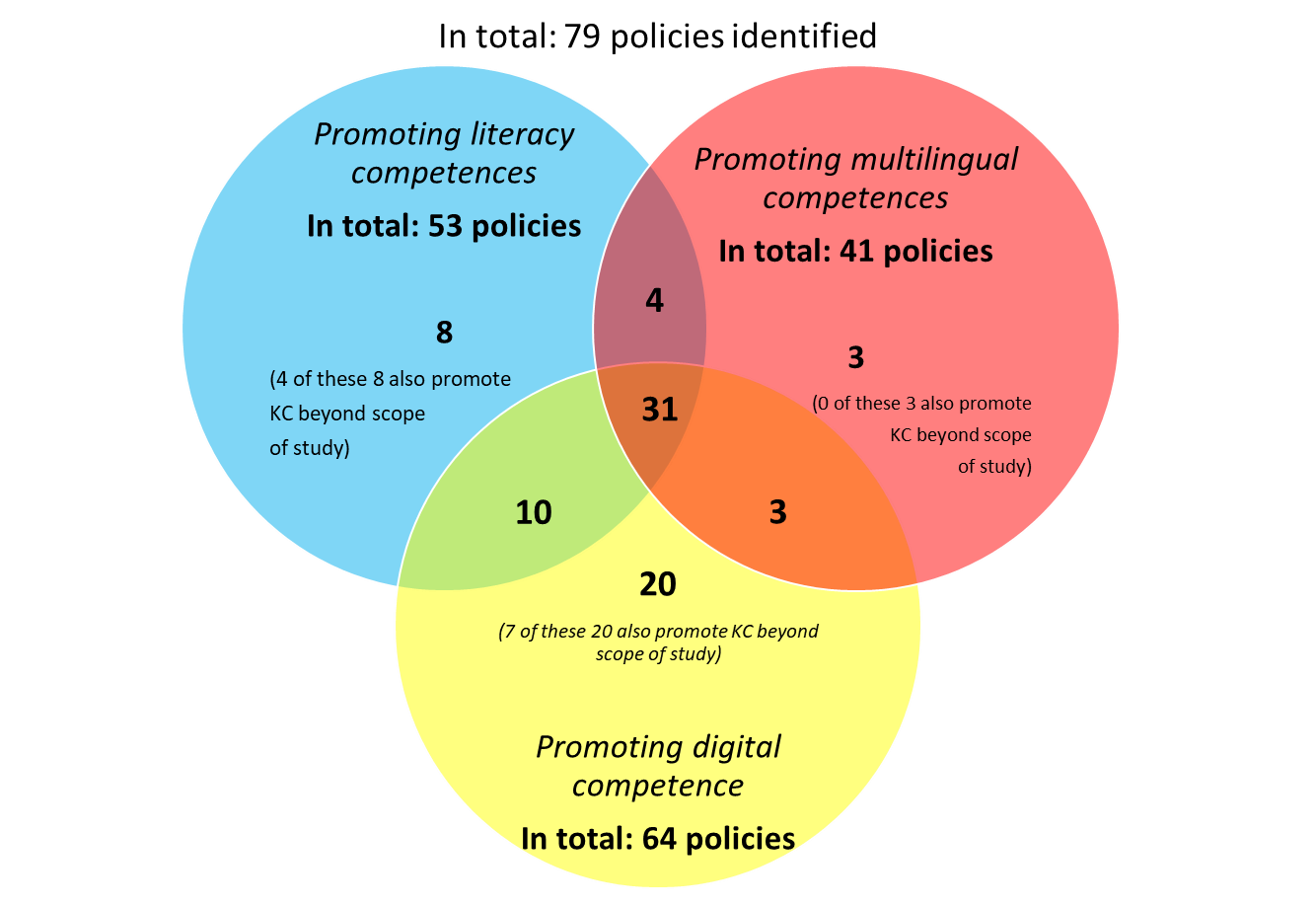

Almost all countries have been found to have policies targeting the three key competences in IVET. A majority focusses on more than one key competence, as illustrated in the following figure.

Figure. National policies promoting literacy, multilingual and digital competences

Source: Cedefop (2020). Key competences in initial vocational education and training: digital, multilingual and literacy. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Cedefop research paper; No 78. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/671030

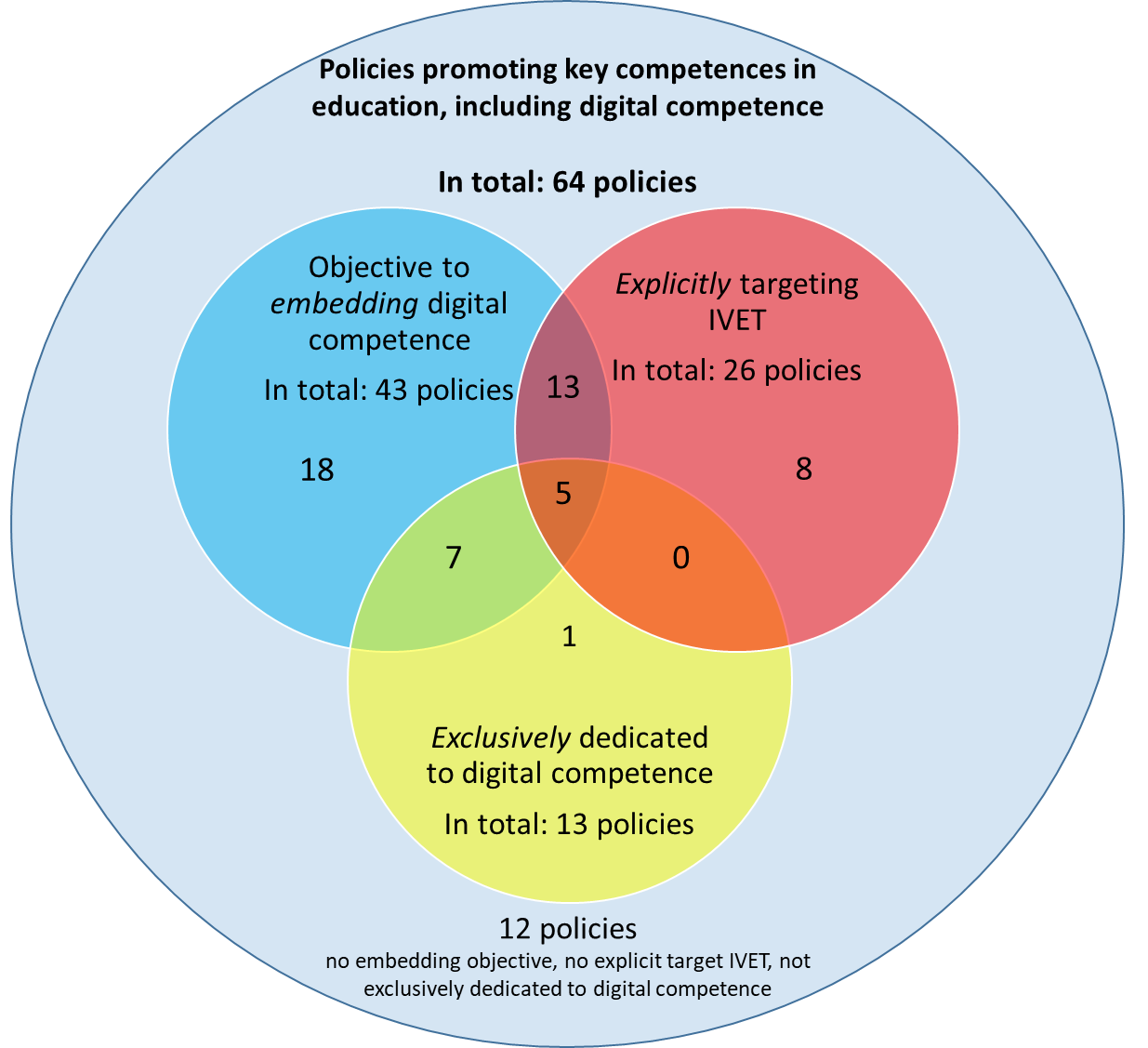

About half of the policies have a wider scope focussing not only on IVET or even education in general, but are linked to broader societal objectives for example employability and social inclusion. The following figure illustrates this for digital competence.

Key characteristics of national policies promoting digital competence

Source: Cedefop (2020). Key competences in initial vocational education and training: digital, multilingual and literacy. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Cedefop research paper; No 78. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/671030.

Most often policies aim to embed key competences through changes to IVET programme delivery, followed by measures aimed at teacher/trainer competences. Moreover, due to being more dependent on the involvement of the various IVET stakeholders, policies that aim at embedding key competences in reference documents and assessment standards can take longer to reach results than policies focusing on programme delivery and teacher training, being slightly less dependent on involvement of various IVET stakeholders.

Qualification type refers to a group or cluster of qualifications within a country that share specific characteristics. Literacy is included in all and multilingual and digital competences in more than 88% of the studied qualification types. Literacy and multilingual competences are usually included as stand-alone modules; digital competence is more often integrated in other modules. However, literacy, multilingual and digital competences are more often integrated in other subjects in apprenticeship-based qualification types.

Multilingual competence is most frequently delivered in an instructor/teacher-centred approach (with few differences between sectors). Digital competence is most frequently delivered by a teacher in a computer laboratory (34%), followed by learning by doing (32%) in which digital competence is acquired in context-specific modules with guidance from a teacher/trainer.

Written and oral tests/ exams or a combination of the two are usually used to assess student performance on multilingual competence during the learning process. For digital competence, assessment is most often a part of the assessment of the subject that digital competence is integrated in. However, written and oral tests are also often used.

Key competences can be learned as a pure key competence or as an occupation-specific competences or as a mix of both. Substantial differences were found between sectors in this context. This was in particular the case for multilingual competence, where in manufacturing this is much more often delivered as a pure key competence or not delivered at all than in the accommodation sector. For digital competence, the differences between the sectors under investigation were very limited.

The great variety in the objectives of policies (also) addressing key competences makes a uniform assessment of their effectiveness and efficiency difficult. Overall, national policies are effective in the sense that they reach their immediate objectives. No important differences were observed between policies that target different key competences, but specific monitoring data on policy implementation and success is hardly existent, also because of the combination with various other topics covered in the policies under investigation. Furthermore, one should note that many of those policies have their roots before the 2006 Recommendation and the publication of other EU agenda-setting documents (Bruges and Riga). IVET systems already included key competences before 2006, As a result, rather than introduce something new, many policies since then aimed to reform an element within the existing situation.

The full research paper can be found on the website of Cedefop.